Homes of Hope

By Harley Walden

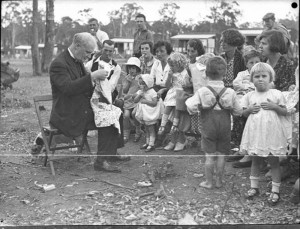

THE year was 1935, Peter Pan had just come off his second Melbourne Cup win (1932-34) the Great Depression rolled over the lives and hopes of millions, an Anglican minister came up with a plan to house some of the families evicted from their homes, often with no means of financial support.

Robert Hammond was archdeacon at St Barnabas’ Anglican Church in Sydney’s Broadway.

Wondering what he could do to alleviate the suffering he saw all around, he invited married men to a meeting in February 1932.

His idea was what he called a ‘consolidated settlement’, a residential development on new land where families of unemployed would help themselves and each other to build, rent and eventually purchase their own homes.

Each would use their skills to help others and after around seven years would have paid sufficient rent to own their houses outright.

To qualify for the scheme a married couple needed to be unemployed, have at least three children and possess a skill useful to the community.

They had to show that they had been recently evicted and make a commitment to joining the community in growing its own food.

Rents were very reasonable and did not need to be paid by those who continued to be unemployed.

The ‘Pioneer Homes’ scheme, as it was originally known, received 800 applications and began with 13 acres near Liverpool.

Although the initiative received little official support, donations from the public enabled a start to be made.

Now comes into the picture, Mr Rodney Dangar.

After his great horse Peter Pan had won his second Melbourne Cup, he learned that Canon Hammond had an option of purchase over ground which added 150 acres to Hammondville.

That made a total area of 210 acres.

Mr Dangar knows good land from bad. He went out and had a look at the soil. “It is good,” he said. “Here men could get something out of the land they tilled. How much?” “£3,750!” Canon Hammond answered, “I’ll let you have it!”

“The option expires tomorrow!” the Churchman mentioned, but Mr Dangar works like his horse raced, without thought of tomorrow.

The ground was made available for closer settlement, the scheme had justified its existence,

Peter Pan, the one horse of the entire world’s horses, had been responsible for a thriving community.

It was a great record of which Mr Dangar was immensely proud.

One hundred and forty pounds put up another house and enabled another poor family to be transported from the hell of dismay to the paradise of hope. Five pounds will give the settler the essential seed and manure for his first year’s work.

Some big men of the turf helped immensely, they helped like gentlemen do, without ostentation, without publicity, giving without hope of reward.

Mr Arthur White of Belltrees, Scone erected a cottage in the early settlement, that was £100.

He went to the settlement and believed in the scheme, he sent five tons of wire netting, which proved of inestimable value to the settlers who kept poultry.

Later he added two rooms to his cottage, great work from the pastoralist-sportsman.

He at least knew what he had done was far greater than charity.

He had given down-and-out brothers opportunities to rehabilitate themselves, he had helped men with nothing to help themselves to economic security, and in helping themselves they had helped others, because to that date the present settlers had repaid £800 of their obligation, which was put into new houses to enable other men and women submerged in economic damnation to make a new start, where every penny they repay is credited to them to make their improved acre their own.

They were the prayers of actions, which made barren fig trees bear fruit for the benefit of the community.

Twenty six homes were completed in the first year. Another 40 homes were built the following year, and another 160 acres was purchased with a generous individual donation.

By 1937, 110 homes were housing families.

Hammondville, as it came to be called after its visionary founder, had a church, post office general store and school by 1940.

A senior citizens facility was developed in later years and Hammondville continued to thrive.

The community grew even further during the war, and many of the men served in the armed forces.

By the end of the war in 1945, most families had already paid off their properties and now owned them along with the acre of land on which they stood.

Hammondville tradition was full of stories about individuals who made great contributions to a unique community.

They included Constance Jewell and her ‘Depression recipe’ cakes, so popular at dances and fundraisers.

Shopkeeper Alf Morley was known as the ‘Mayor of Hammondville’ because of his popularity.

Alf opened the town’s first shop with a 100-pound loan from the founder and provided generous terms of payment as well as free ice-creams for the kids.

Other notable people from the community included property developer Jim Masterson and politician John Hatton, Reverend Bernard Judd and his wife Ida, had a long connection with Hammondville and were prime movers in establishing various local institutions, including the Girl Guides and the Senior Citizens Home.

Robert Hammond’s vision and energy were recognised in in 1937 when he was awarded an OBE, he died in 1946 at almost 76 years of age.

scone.com.au

scone.com.au